A single parent of a toddler sent me this message last week. “I know that this isn’t a huge deal and I have a lot of time to talk to my daughter about sexism and gender, but it all of a sudden feels very urgent.”

“Why is that?” I asked. She went on to share that three boys at daycare had told her daughter that “Girls can’t play this game with us because they won’t like it.”

“Ugh,” I responded. “How did your daughter respond?”

“She told them that she loves robots and they ended up playing together. Again, not a huge deal. But I can just feel the stakes rising as they get older,” She replied.

“It’s amazing how early kids start using these categories to include and exclude each other,” I said. “And honestly, it’s never too early to start talking about it.”

Learning race and gender

Starting out right away, babies and toddlers are learning about the world and wondering “What is important here?” It doesn’t take long for them to learn that race and gender matter. Dr. Jacqueline Dougé, an author of the American Academy of Pediatrics statement on the impact of racism on child health, reminds us that toddlers are already making observations and organizing their world based on things they can see. They learn quickly that some categories matter a lot more than others, with race and gender at the top of the list because they are constantly cued to their significance. For example, most adults start teaching binary categories right away by labeling things and activities as either “boy” or “girl” over and over again throughout the day.

Once children learn to pay attention to these categories, they start actively seeking clues about what their gender and racial identities and possibilities mean. They are linking their own feelings and experiences with observations of what they see around them, what they guess to be true, what they absorb in the toy aisles, what they see on screens and in books, and what they experience with family and friends.

In the absence of explicit conversations and experiences that disrupt rigid gender roles and racial bias or that nurture gender freedom, anti-racism, or cultural pride, children quickly draw conclusions that conform to stereotypes. The stakes are high. Children as young as four years old show clear biases at the intersection of race and gender. Notably, children’s responses to Black boys were less positive than to Black girls, white boys or white girls. In other words, race and gender bias are already entangled before elementary school.

We’ve come a long way on rigid gender roles. Sort of.

“Did you know that women used to have to make coffee for their husbands EVERY MORNING?” my nephew asked my sister-in-law after watching an old advertisement from the 1950s in health class. Incredulous and before she could respond, he was quick to say “I mean, why doesn’t he make it HIMSELF if he cares so much about it??”

My nephew’s quick analysis of this commercial was adorable and comforting. We have certainly come a long way when a ten-year-old is quick to point out the egalitarian solution to morning routines.

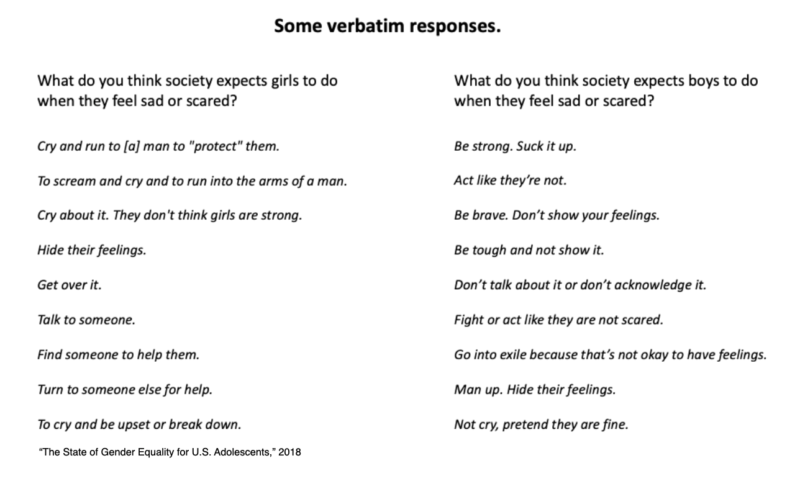

Yet celebrating “how far we’ve come” masks the alarmingly persistent realities of gender bias and rigid gender roles among young people. Here are some verbatim responses from a survey of adolescents called “The State of Gender Equality for U.S. Adolescents.”

There is plenty of evidence that the rigid gender binary and racialized gender bias are alive and well in the United States. For example, Harvard’s Making Caring Common Project recently found that teenagers were most likely to give more power to the school council if it was led by white boys. The same study found that forty percent of teens who identify as boys and twenty-three percent who identify as girls prefer male over female political leaders. Of course these data aren’t just about political aspirations or electability. A recent poll found that seventy two percent of boys say they personally feel pressure from parents, teachers, or society to be physically strong and less than half of boys and men with mental health challenges seek help.

The stakes of rigid gender roles are high.

Unfortunately for our kids, gender bias and rigid gender norms don’t just limit how they think about the world and its possibilities. It has a clear impact on their health and safety.

A mountain of research has found that when young people internalize narrow gender norms, they have lower outcomes related to mental and physical health, education, and economic security. In 2018, the American Psychological Association issued ten new practice guidelines for working with boys and men in response to the toxic effects of “traditional masculinity ideology” on their mental and physical health. If long term health outcomes don’t motivate us, research also shows that traditional masculinity is linked with attitudes that are more tolerant of dating and gender violence in early adulthood. Finally, gender creative or transgender kids too often experience exclusion, bullying or violence for transgressing rigid ideas of what it means to be a boy or a girl.

Engaging children in disrupting rigid gender roles.

Children are absorbing the lessons of gender and race early and often. As developmental psychologist and gender researcher Rebecca Bigler notes, “If adults don’t explain why differences exist, kids make up their own explanations.” Here are just a few ways to get started with young children:

- Get curious about the stories you’ve inherited as a parent. Ask yourself questions like, “When was the first time you thought of yourself as having a gender? Do you remember a time when you felt rewarded or punished for acting in alignment (or not) with a gender role? How was that related to other parts of your identity like race, class, or ability? Do you remember a time when you felt powerful or proud because of your gender? What lessons did grown ups teach you about gender?”

- Explore how race, class, ability, religion and other facets of your child’s identity intersect with one another and overlap. For example, you can help your child understand which groups they belong to and what makes them unique through storytelling and conversation. These conversations help children unlearn, embrace, express and advocate for their multiple identities.

- Language matters. Research shows that routine and unnecessary references to the gender binary reinforces narrow gender roles. Instead of, “Which boys and girls do you want to invite?” try, “Which children do you want to invite?” Try using gender inclusive language (like firefighter and parent).

- Engage in your child’s observations. Dr. Bigler suggests that rather than shutting down your child’s observations about skin color or gender, engage with them and expand their understanding. For example, “You’ve noticed that lots of kids who identify as girls in your class have long hair! Do we know any boys with long hair? How about girls with short hair? Now you’ve noticed that different children have really different kinds of hair! What do you like about your hair?”

- Encourage mixed gender friend groups. Many parents notice that their children start to “self segregate” by assigned gender. You don’t need to stand in the way of growing friendships, but do encourage all gender activities when it makes sense.

- Don’t ignore the influence of media. Read and talk about books that interrupt stereotypes. As children get older, use Common Sense Media’s Gender and Digital Life Toolkits to choose shows that disrupt narrow gender roles and offer more expansive stories to kids.

- Talk about consent and body autonomy early and often. Gender roles aren’t just about toys, clothes, and jobs. Gender and race often dictate who gets to control their body, choices, and space from a very young age. These tips for educators are relevant at home as well.

- Support your child’s emotional literacy. Every child deserves to express and identify a whole range of emotions from anger to sadness to joy.

- Engage your children in disrupting gender bias at home as training grounds for life. Harvard’s Making Caring Common Project suggests involving your kids early in tackling bias together by talking openly about:

Household chores and who does them.

How decisions get made.

Who takes care of who.

Fill in your own: ___________________ - Get the support you need. We bring our own histories and challenges to our parenting. Don’t forget to “put on your own oxygen mask” first.

- What is missing? What would you add to this list?

Let’s partner with our kids to build new understanding and skills.

Clearly talking early and often is key. But so is playing, practicing, and exploring. Research shows that it is not enough just to show children expansive gender roles and diverse characters in books and shows and hope they absorb the lessons. Instead, we need to talk in age appropriate ways about gender bias and sexism and engage our kids as active learners.

Dr. Bigler ran an interesting school-based experiment that points to what it actually takes to prepare children to confront bias. She found that with children in early elementary school, reading stories about interrupting sexism was not as effective as actively teaching the same interventions. For example, she actively engaged one group of children to spot six different ways sexism shows up (things like “girls can’t play this game!”) and then rehearsed and role-played six different memorable responses (things like “You can’t say, girls can’t play!”). This group of kids was far more likely to actually confront sexist dynamics on the playground than the children who were read to.

At home, these lessons might sound a little different and they don’t happen in one sitting. They don’t happen in a lecture. They look different in each of our households depending upon our culture and our identities. They happen over Cheerios, through screen time, and in conversations about how we know what kinds of games kids like and don’t like. They happen when we partner with our kids in both mundane moments and in building movements for change.