During a virtual presentation a parent recently asked, “We’ve gotten into some really bad screen time habits during the pandemic. How do we make sure they don’t stick when this thing is over?”

I smiled to myself because at that very moment my own kids were holed up in our unfinished basement with iPads while I was delivering the workshop.

“We have been making some tough choices with limited options for a long time now haven’t we?” I responded.

The pandemic is not over. As expected, instead of a switch flipping to indicate COVID’s end, we are embarking on a long and uncertain ramp towards safer interactions and the return of offline activities. There are plenty of things we’re anxious to leave behind as restrictions lift.

When it comes to screen time though, we would be wise to pause and take a moment to reflect within our families about what we want to be sure to carry with us in the months to come. In other words, we don’t just want to break “bad” habits that have crept in; we want to maintain and build on the positives we’ve picked up.

Living through COVID has made us painfully aware of the limitations of screens. We’ll be glad to leave some things behind– anxiety from too much scrolling, risks of long unsupervised hours online, and chronic multitasking. But it has also given some parents a front row seat to the connective and protective power of their kids’ digital habits and windows into the ways technology allows kids to learn, connect, participate, and collaborate.

For too long, parents have received a steady drumbeat of warnings about the harms that technology is having on children. The implication, therefore, is that parents should serve as remote controls only in charge of changing content and turning devices on and off.

The research, however, paints a different picture. Yes, kids absolutely need boundaries and age-appropriate content. They also need adults to be their digital mentors as they navigate ever-expanding digital spaces – adults who take interest in their digital lives, notice their digital strengths and vulnerabilities, and help them practice critical literacies and skills.

Pause. Reflect. Shift.

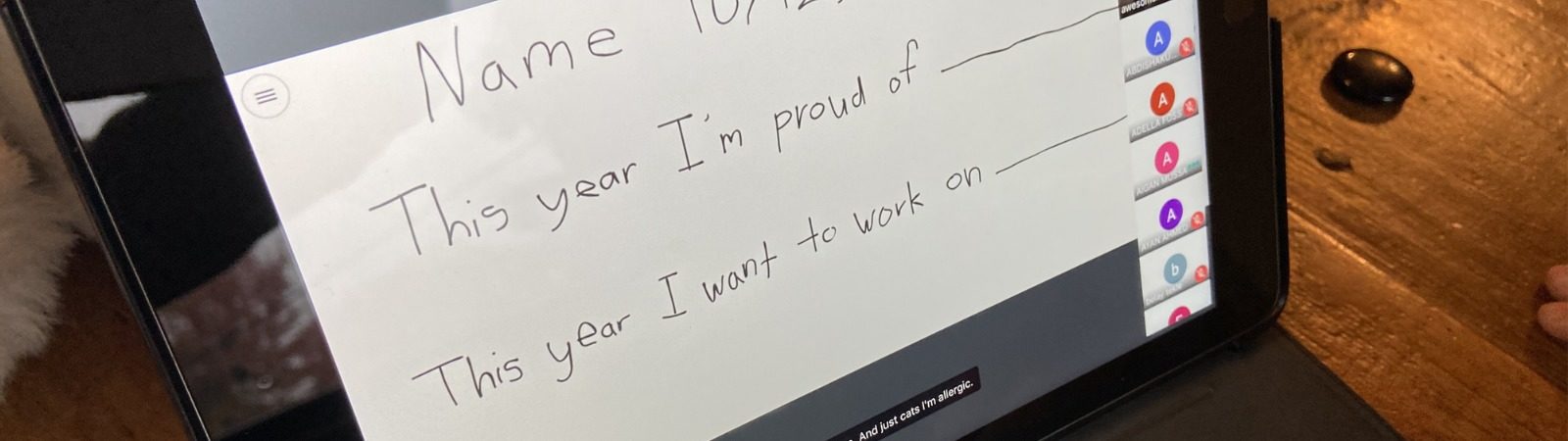

So my recommendation is to avoid seeing upcoming screen time transitions as simply “breaking bad habits.” Instead, let’s involve our kids in a bit of reflection about questions like:

- What have we learned this year?

- When does tech help us? Who benefits from how we use tech?

- When does tech get in the way or hurt us?

- Why is it so hard to unplug?

- What do we want to keep doing?

- What do we want to shift, replace, or let go of?

As we have these conversations, we might learn something about our own habits from our kids. For example, one of my kids recently shared that he “hopes we keep playing Minecraft together” and agreed that when school is back to normal he hopes no one has to work in the evening anymore.

These reflections won’t happen in one giant, serious talk. It will happen over time as we negotiate changing trade-offs, as offline possibilities re-emerge, and as we create new boundaries, create new screen time habits, and make family agreements. But this transition will go better if we do it with our kids instead of to them.

As I reflect on my own experiences and conversations with families across the country this year, here are four things that I hope we do take away from this screen-intensive time. May we use these insights from research as guideposts as we navigate the long and uncertain ramp out of the pandemic.

Screen time shame isn’t helpful. It never was.

Too often, screen time choices have been laden with shame or guilt. Shame triggers our stress response and makes it hard to explore the function and impact of specific digital habits. During COVID, a lot of parents let go of screen time shame out of sheer necessity. In some households, this has decreased unnecessary conflict and freed families up to be more honest about how things are going. When we stop trying to decide whether our approach to screen time is “good or bad,” we can start to look at the whole family system including our kids’ mental health, sleep, movement, connections, and habits.

Pandemic or not, every family has always had unique strengths and vulnerabilities based on their own identities, circumstances, and kids. Let’s keep giving each other the grace we’ve extended each other during this time and stay focused on what matters: our kids’ wellbeing.

Connection is key.

Researcher Dr. Jane McGonigal has observed that young gamers who use games “to make their world better” have better outcomes than gamers whose goal is, “to escape their world.” In other words, it really matters if they are gaming together or alone.

We human beings are hardwired to connect. We’ve just spent a year reaching through screens to learn, watch babies learn how to walk, share with elders, and laugh with friends. We’ve also felt the acute and painful realization over and over again that these are no substitute for face-to-face sharing and long hugs. Teenagers have been navigating this tension for years. They can teach us how to use screens to extend and deepen real world friendships. They can show us how they have overcome logistical barriers or created online spaces in the absence of positive youth spaces in their communities. And we can talk about how important face-to-face time is for adolescent wellbeing.

Let’s continue to be more open to the protective power of online relationships and acknowledge that they meet a real need for our kids. Let’s also advocate for and create more meaningful opportunities for face-to-face time. We can advocate for the latter without dismissing the former.

How we connect matters.

We may be hardwired to connect, but how we connect matters when it comes to our wellbeing. For example, racist, sexist, or ant-Semitic interactions online not only mirror and magnify toxic interactions offline but have a significant negative impact on mental health. Likewise, collaborative and creative play with peers has been protective against depression while unwanted online attention and online drama has caused pain and isolation. While these examples might seem obvious they bear remembering because they point to the critical work ahead. Logging off our computers is one thing; building healthy relationships is another. As we move back towards each other it is worth thinking about how we build skills like communication, anti-racism, empathy, and accountability that form the basis of healthy connections online and offline.

Our role is so much more important than simply turning screens on or off.

Many of us haven’t had time for reflection. We haven’t had the bandwidth to consider how we would construct our ideal digital lives. But that doesn’t mean that we haven’t been learning important lessons about what our kids are capable of and what we need from each other during this year of digital immersion. As we start logging off more often, let’s be sure to continue showing up in our kids digital lives.

Some of our kids will throw their devices aside and run back into the world as soon as it is safe and possible. Others might want to linger in the basement on their iPad. Each of us will benefit from pausing and reflecting as we redefine normal. What do we want to keep doing? What do we need to shift and replace? How are we going to stay connected?